The Historical Archive of the Hospital of the Innocents is an essential place for anyone wishing to do genealogy research in Florence. It is an indispensable resource for all those seeking to trace their own origins. It is indeed useful for any research in the fields of welfare, economic, medical, and art history from the fifteenth century to the present day. If your last name is Innocenti or Degli Innocenti or something similar, your origins are probably rooted here. The Historical Archive of the Hospital of the Innocent preserves an extraordinarily rich body of documentary material, unique in its chronological completeness and variety of content, which allows us to reconstruct the history of the institution. The archive is located on the ground floor of the Istituto degli Innocenti in Florence, in what was once the men’s refectory. It contains more than 13,000 archival units arranged in an elegant cypress-wood structure inspired by the model of Renaissance libraries.

Genealogy Research in Florence at the Historical Archive of the Hospital of the Innocents

The Historical Archive of the Hospital of the Innocents is a great instrument to do genealogical research in Florence. The evolution of the concept of childhood over the centuries and the life paths of the girls and boys received by the hospital from the late eighteenth century onward are documented here. The most remarkable series useful to a genealogical research in Florence is the series Balie e bambini (“Wet Nurses and Children”), consisting of hundreds of registers bound in parchment and leather, preserving the memory of all the children received by the hospital from 1445 onward. In these registers, each page contained information relating to a new arrival, beginning with the details collected at the time of admission that were necessary for any possible later recognition by the parents: the day and hour of abandonment, information on baptism, the names of the parents or of the person who left the child, and the presence of any notes or objects. On the same page, over time, the most important events in each child’s life were recorded, allowing us today to reconstruct the biographies of the hundreds of thousands of children received by the Innocenti over the centuries.

Family records at the Historical Archive of the Hospital of the Innocents

Alongside this series are the daily annotations of scribes, chamberlains, and priors, who over time contributed to the compilation of numerous books of income and expenditure, debtors and creditors, journals, memorials, as well as records relating to the farms owned by the institution. Finally, mention should be made of the Estranei series (literally, “strangers”), which brings together family and business records that came to the archive along with the inheritances of merchants and bankers active between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, including the Gambini, the Salutati, and the Gondi families. This material constitutes documentation of particular interest for economic and social history. In these books, Renaissance entrepreneurs recorded events connected with mercantile practice, as well as family matters such as the births or deaths of children, their placement with wet nurses, and later the most significant moments of their lives.

The Foundation of the Hospital of the Innocents

Florence holds the distinction of having built an institution dedicated exclusively to foundlings, also known as gittatelli. The merchant Francesco Datini, a native of Prato who lived in Florence, allocated the considerable sum of 1,000 florins for this purpose in his 1410 will. In 1419, the Arte della Seta, one of the city’s most important guilds, used Datini’s bequest to purchase land and begin construction of the new hospital, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi. In 1421, the consuls of the guild were appointed patrons, and the municipality authorized the establishment of a new hospital named Santa Maria degli Innocenti, in reference to the Massacre of the Innocents described in the New Testament, granting it the same privileges as the city’s older charitable institutions. Therefore, in 1445, with the admission of the first newborn—a girl named Agata Smeralda—the charitable activity of the Innocenti began. The Spedale degli Innocenti is considered the first orphanage in the world. As a matter of fact, until the XV century in Florence the main hospital of Santa Maria Nuova took care of orphans, pilgrims and sick people.

The tour of the Hospital of the Innocents in Florence

Definitely off the beaten tracks, the tour of the Hospital of the Innocents in Florence is extremely touching. Milestone of Renaissance architecture, being considered the first entire building projected by Filippo Brunelleschi along classical lines. The tour of the Hospital of the Innocents in Florence represent a fundamental witness of social welfare and charity aimed to take care of childhood. Even if you are not doing genealogy research in Florence, this museum is absolutely worth-seeing. The phenomenon of child abandonment, widespread since antiquity, intensified in Italy between the 13th and 14th centuries, at the peak of demographic growth, particularly in cities. The causes were numerous: wars, famines, plagues, and poor harvests. During the 15th century, the care of abandoned children became a charitable activity carried out by major urban hospitals, which had originally been devoted solely to the care of the sick and the sheltering of pilgrims. The Hospital of the Innocents is nowadays also a museum. We can learn about its history, art and architecture, thanks to several masterpieces, such as The Adoration of the Magi by Domenico del Ghirlandaio, the teacher of Michelangelo.

Marks of Identification and the Fate of Foundlings

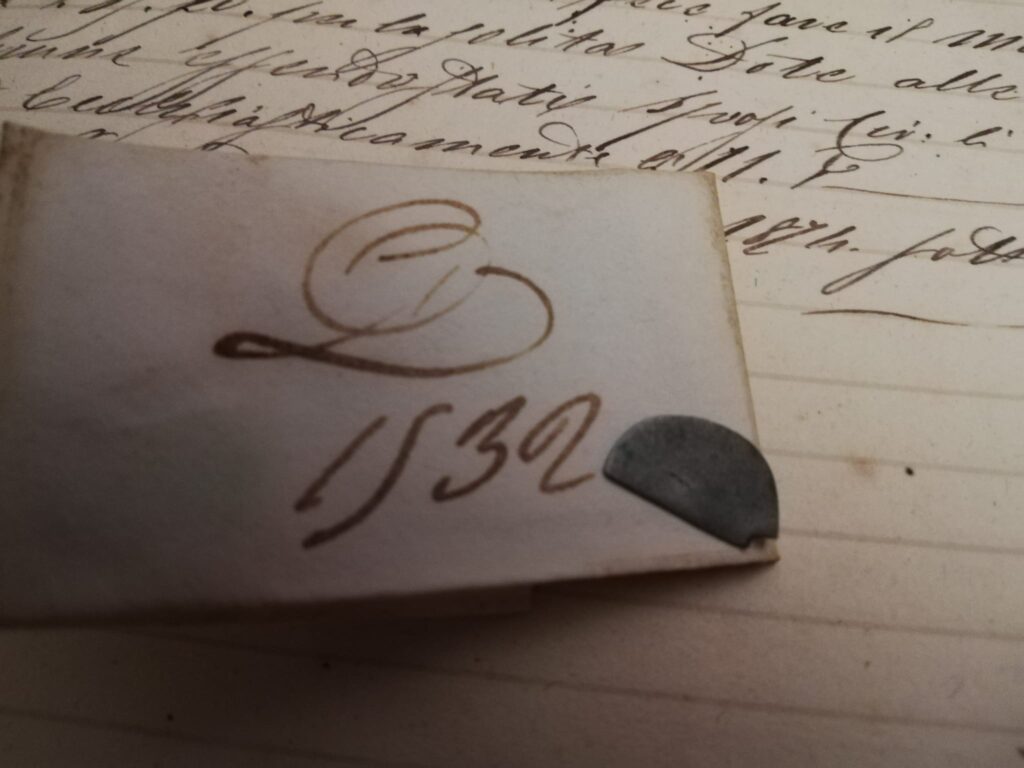

One hundred and forty nineteenth-century tokens are displayed in a room of the Museo degli Innocenti to evoke a practice followed by parents in every era and throughout all Italian regions. Placing objects or written messages among the swaddling clothes of children destined to be abandoned was common. These are the so-called marks or tokens, which defined the children’s origins and their belonging to a family group, a social class, a village, or a city. This is undoubtedly the most touching part of the museum. The Historical Archive of the Innocenti preserves thousands of messages and small objects. Actually, there are medals, coins, rings, clasps, holy cards, small crosses, pieces of colored glass, buttons, scraps of fabric, or whatever could be recovered before entrusting the newborn to the hospital. More deliberate and propitiatory was the choice of coral, red ribbons, and beneficent stones such as carnelian and agate. These tokens would have allowed parents to identify their children should they return to reclaim them. In fact, it was a hope for future recognition and the reconstruction of identity that accompanied the Nocentini throughout their lives.

The “Wheel of the Innocents“

In 1465, more than 200 newborns were admitted in a single year. By 1484, the hospital housed around one thousand children. Girls were in the majority, as they were considered less suited for labor and more costly, since a dowry was required for marriage. Their number therefore continued to grow over the centuries. Upon admission, newborns were carefully examined by the wet nurses on duty, who recorded their sex, clothing, and any objects found with them in the pila. The pila was a basin resembling a holy water font in which swaddled infants were placed anonymously. In fact, it was set into a rotating wheel that allowed them to be brought inside the building unseen. As said, particular attention was paid to identifying tokens accompanying the children—small objects with propitiatory and above all identifiyng value.

The Hospital of the Innocents: a few numbers

The babies were then cared for by internal wet nurses, known as “di casa,” while awaiting transfer to women in the countryside for breastfeeding. Infant mortality, however, was extremely high. around 50%, especially during the first year of life when weaning began. Not all surviving children returned to the institution at the end of their nursing period: some remained with the families who had taken them in, others were adopted or apprenticed to artisans to learn a trade, while girls entered domestic service in wealthy households to save for a dowry from their wages. As early as 1465, annual admissions numbered around 200. By 1484, more than 1,000 children were being assisted, with female abandonments surpassing those of males, leading to the progressive growth of the female community. In 1627, the hospital reported 1,120 mouths to feed among women, girls, and boys, and 88 among wet nurses and infants. In 1873, shortly before the closure of the foundling wheel, admissions reached 2,318, more than half of whom were legitimate children. It is estimated that from the first abandonment in 1445 until closure in 1875, hundreds of thousands of children passed through the Innocenti.

The closure of the Hospital of the Innocents

After Italian unification, the need to put an end to the abandonment of legitimate children in charitable institutions became increasingly urgent. Between 1867 and 1874, foundling wheels were closed in Ferrara, Milan, Turin, Novara, Rome, Cosenza, Genoa, and Naples. On June 30, 1875, the wheels of Florence, Venice, Verona, and Siena were also abolished. From 1890 onward, the Innocenti became a public charitable institution by law, inaugurating an important season of hygienic and health reforms and achieving a high standard of child care. A maternity hospice for impoverished women in labor was also opened, and a midwifery school was established for young women wishing to practice the profession. In 1900, the Innocenti were invited to participate in the Paris Universal Exposition in the field of health care and prevention.

Your Genealogy Research in Florence: the Last Names of Children

Over the centuries, the surnames assigned to children abandoned to public assistance varied according to geographic area. So if you want to conduct your genealogy research in Florence, your last name is important. In Florence, children were given surnames derived from the hospital itself: Innocenti, Degli Innocenti (or Degl’Innocenti), and Nocentini. In Campania, especially in Naples, the surname Esposito—with variants such as Sposito, Esposto, Esposti, and Degli Esposti (or Degl’Esposti)—was the most widespread and explicitly indicated that the child had passed through the foundling wheel, being “exposed” to public charity. Proietti or Proietto, derived from the Latin proicere (“to throw”), were common in Lazio, where the wheel was called rota proiecti. In Emilia-Romagna, surnames such as Casadei (“from the house of God”) and Incerti or Incerto, from the Latin incerti patris, were used. Even more explicit were Ignoti, Ignoto, Di Ignoti, or Di Ignoto, widespread in Sicily and Piedmont. In Sicily, the surname Trovato was commonly used to emphasize the accidental nature of the child’s origins. In Genoa, surnames such as Casagrande, Della Casa, and Della Casagrande referred to the institution itself, the “Great House” that had taken them in. Names such as Diotisalvi, Diotaiuti, Diotallevi, and Pregadio were instead assigned with auspicious intent.

Last Names of Children Abandoned at the Hospital of the Innocents

From 1812 onward, children abandoned at the Spedale degli Innocenti—well ahead of other Tuscan hospitals—began to receive proper surnames, distinct from the traditional Nocentini, Degl’Innocenti, or Innocenti, which had previously exposed their illegitimate origins and caused profound social stigma. By sovereign decree of May 9, 1817, all children abandoned in any orphanage within the Grand Duchy of Tuscany were likewise provided with a surname. The Ministero delle Creature, responsible for drafting the records, assigned each new arrival—after the baptismal name (usually more than one)—an invented surname, which could not be indecent or ridiculous, nor replicate that of an illustrious family. This is how the most imaginative last names started: Braun, written with an Italian spelling; Lander, making an Italian last name (Landi) sound like foreign, adding -er; or Fronges, literally “segno RF” read backwards (sign RF), from the initials RF embroiders on the toddler’s cloths. This is why the Hospital of the Innocents might be a good starting point for your genealogy research in Florence.

Contact me if you want to know more!