The ancient Florence Jewish Community

There is no certain news about the origins of Florence Jewish community after the foundation of “Florentia” as a Roman colony (I century BCE). Nevertheless, the first Jews probably arrived to Florence at the dawn of Christianity. They settled on the left bank of the Arno river, near Ponte Vecchio. It was at the end of Via Cassia, the main arterial road between Florence and Rome. If you are curious about this topic, you can take a look at our Jewish Florence Walking Tour. We will talk in-depth about the relation between Jews and Christians in Florence during the Renaissance.The original Florence Jewish community lived in Via dei Giudei (literally, Street of the Jews) at the corner with Borgo San Iacopo. The first synagogue was likely inside the Belfredelli tower. It is a tower-house of the 12th century, still existing. The earliest documents regarding the origins of Florence Jewish community go back to the beginning of the 1400s. It was when the fervent city’s trade required the presence of the Jewish money lenders. Canon Law, based on several passages of the Old and New Testament, condemned the concession of any interest on the loans. However, during the Middle Ages, this precept was at odds with the urging need of cash to favor the trades. Furthermore, many thought that it was unfair to lend money for free.

The Jews in Florence as pawnshops holders

Did the lender have any right to receive a compensation for the time he deprived himself of his money? Could he cover the risk of not seeing his loan refunded? The Christians tried to cheat the system entrusting the money lending to the Jews. In fact, they were not part of Christendom. They were consequently not subjected to Canon Law. In general, Italy was not characterized by systematic antisemitic waves, unlike the rest of Europe. In Paris, Christian authorities burnt the Talmud on the stake in 1240. Moreover, the Jews were expelled from many French regions and England in 1289-90. The belated presence of the Jews in Florence contrasts with the general trend throughout medieval Europe to recur to Jewish pawnbrokers. Rabbi Umberto Cassuto (1917) states that Florence during the XIV century was so rich and economically vivid, that the money lending was managed by the Christians. Actually, the Church’s ban of usury was not respected for many years. One could confess the usury crime on his death bed and leave generous sums to religious institutions, like hospitals, convents or churches. Doing so, he had his soul rest in peace far from the flames of Hell.

Christian and Jewish money lenders

The plague of 1348, commonly called “Black Death”, was a turning point for all European Jews. The Church accused the Jews almost everywhere of poisoning the water wells to spread the disease. The pestilence killed approximately one third of the European population. One more ignominious accusation was the Jews’ ritual homicide of Christian children. This happened especially during Easter, that symbolically repeated the sacrifice of Jesus. The antisemitic stereotype was reinforced in the 1300s, when “the Jew” became the enemy of Christian society. England exiled the Jews in 1290. France did it in 1322, Spain in 1492 and the Kingdom of Naples in 1541. In 1493 the king of Portugal forced the Jews to convert to the Christian faith. The Portuguese Jews were called marranos. The only exception on the map of Europe was represented by northern and central Italy. Here the Jews could continue to live and develop their communities, like in Florence.

Christians and usury

At the beginning of the 14th century, the members of the Guilds of Florence (medieval associations of workers) had to participate in an expiatory rite called “forgiveness of usuries”. They begged for God’s absolution to forgive their sins of usury. In 1367 the Guild of Bankers introduced a new rule in its statute. Whoever lent money at high interest was punished with a fine of 100 lire. All Florentine Guilds prohibited the practice of usury in their regulations. In 1396, the municipality of Florence finally authorized the Jews to move to the city. They had the explicit task of lending money at a fixed interest rate of 15%. Christian lenders applied a rate of 30% instead. They were obviously hostile to their Jewish competitors. In 1430, the Florentine government decided that any Jewish banker could work in Florence, only if the interest rate was not higher than 20 %. The purpose was to make credit accessible to even the poorest citizens.

Florence Jewish community and the Medici family

The first contract between the Florentine government and the Florence Jewish community was officially stipulated in 1437. It’s not a coincidence that Cosimo the Elder de’ Medici (1389-1464) was rising to power in the very same years. He was openly in favor of the Jewish pawnbrokers. He wanted to increase the cash liquidity necessary in everyday commerce. During the 15th and 16th centuries the Medici family behaved favorably toward the Jews, both economically and culturally. To know more about this incredible family of bankers and patrons of the arts, take a look at my Medici Family Tour!

Cosimo the Elder supported the State’s ordinance of entrusting the money lending to the Jewish pawnshop holders. It was better that the Jews did “the dirty work” of lending money to the commoners through their pawnshops at a usury rate than the Christian Medici family. They preferred to do much more profitable business with kings and popes, indeed. Generally, when the Medici family was in charge of the city’s government, they supported the Jewish money lending. When the Medici experienced a period of crisis the Jewish bankers were persecuted or banned.

Lorenzo the Magnificent and the Jews

The Florence Jewish community also enjoyed the protection of Cosimo’s grandson, Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-1492). We know that he went on vacation in Val d’ Orcia (Bagno Vignoni) with a group of Jewish friends. They played, discussing philosophy and having fun. One of them was probably Emanuele di Bonaiuto, born in Camerino (Marches region) between 1420 and 1430. He moved to Florence in 1456 when he married Gemma da Fano. Once in Florence, he was known as Manovellino. He became one of the richest bankers of the Florentine elite. Furthermore, Emanuele da Camerino was famous for being a great scholar. His library was one of the biggest in Florence. He had friendships with the most prominent intellectuals of his time. Emanuele died in 1498 and his last will shows clearly which was his attitude toward both Christians and Jews. Besides guaranteeing his wife Gemma’s economic wealth, he designated a huge sum of money to providing an education to the poor Jewish kids and a dowery to poor girls of both faiths.

Florence Jewish community, the Renaissance and the Cabala

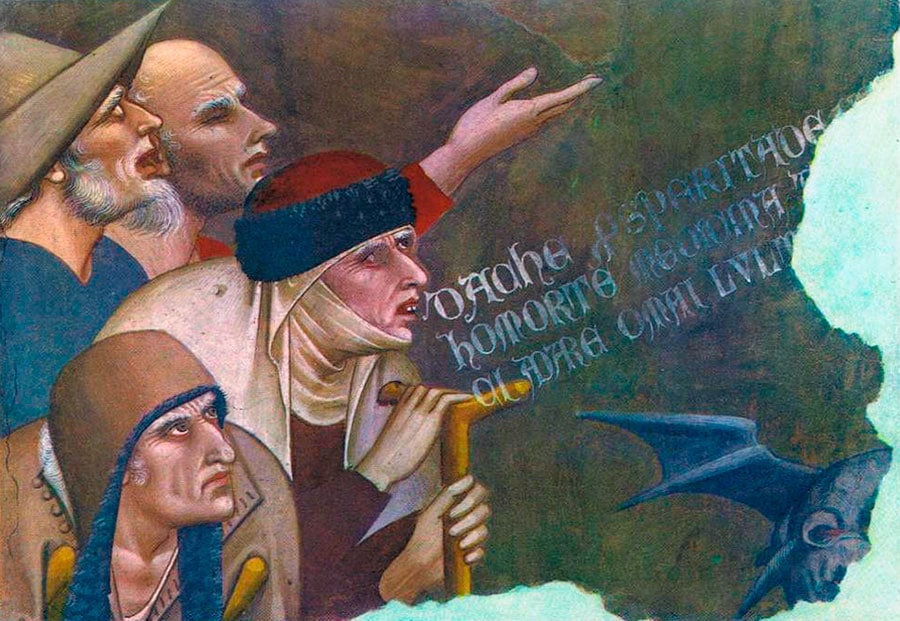

It’s well known that the Jewish mysticism and the Cabala attracted the Medici. The Renaissance was a period of great cultural connexion between Jews and Christians. Jewish and Christian cultures were related through a strong and mutual sense of attraction. The Platonic Academy founded by Cosimo the Elder and Lorenzo the Magnificent was a great occasion of exchange between the Christian and Jewish worlds. One thing was central to allowing the Christian humanists to study the Cabala. First of all, they had to learn the Hebrew language. The role of the Florence Jewish community was to enable the Christian patrons to learn about older, and for them inaccessible, forms of thought. The most important translators of Jewish texts during the Renaissance were Flavio Mitridate (1450-1489), Yohanan Alemanno (1435-1503) and Elia Del Medigo (1458-1493). Florence was a center of Hebraisms, thanks to Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459), Ambrogio Traversari (1386-1439) and Giannozzo Manetti (1396-1459). Manetti had a Hebrew teacher who lived with him and talked to him only in Hebrew for two years. He was a Jew converted to Christianity. In fact, even though the Christian society was somehow open to the Jewish culture, the superiority of Christian faith was undiscussed.

Florentine Humanists and Cabala

Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499) was the greatest connosseire of the Jewish culture in Florence, especially of Cabala. In Hebrew quabbalah means “received tradition”. It indicates a particular form of mysticism rooted in 12th-century Provence and in 13th-century Spain. Renaissance intellectuals tried to get the deepest sense of God’s creation through a mystic interpretation of the Holy Scriptures. However, this cultural vicinity between the two cosmos caused a certain alarm in the Jewish community. It was a risk to the Jewish identity because a profound knowledge of their world could be a perfect expedient to try to convert them to the Christian faith.

Get to know more about the connections between Jews and Christians in Renaissance Florence and book your Jewish Florence Walking Tour! Contact me by email and let’s create together your customized experience in Florence!